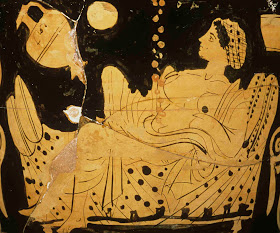

Starting, for no particular reason, with

this:

And I was recently rereading James Fitzjames Stephens, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.

Stephens is obviously the ‘conservative’, rebutting Mill, the

‘liberal’. But in a lot of ways their positions don’t track contemporary

notions. For example, Stephens is very opposed to the state tolerating

lots of little heterodox churches. No. The state should do its best to

figure out which one is best and sponsor it. (Theological spin on

industrial policy and ‘picking winners’.) The proof, offered in passing:

anything else and you’ll end up having to tolerate Mormonism. Which is obviously not on.

Well, there is a particular reason, which I'll make plain in a moment. But first, I want to tie it into

this. And raise the seemingly unrelated point that the reason we are seeing religion in decline around the world (to the extent that we are, and I'm still not in despair or even discouragement over that "decline") is for the very reason that theology has been deposed by science as the source of all that is reasonable.

In other words, it's a simple matter of education. What you teach people is what they will consider a valid baseline; and if you no longer teach them that theology is the mother of all the sciences, then eventually religion itself will lose any allure it might once have had. Which, to the ignorant and small minded, is an improvement. But

look again.

Children

In the ancient world children were routinely left to die of exposure

-- particularly if they were the wrong gender (you can guess which was

the wrong one); they were often sold into slavery. Jesus' treatment of

and teachings about children led to the forbidding of such practices, as

well as orphanages and godparents. A Norwegian scholar named Bakke

wrote a study of this impact, simply titled: When Children Became

People: the Birth of Childhood in Early Christianity.

Education

Love of learning led to monasteries, which became the cradle of

academic guilds. Universities such as Cambridge, Oxford, and Harvard all

began as Jesus-inspired efforts to love God with all ones' mind. The

first legislation to publicly fund education in the colonies was called

The Old Deluder Satan Act, under the notion that God does not want any

child ignorant. The ancient world loved education but tended to reserve

it for the elite; the notion that every child bore God's image helped

fuel the move for universal literacy.

Compassion

Jesus had a universal concern for those who suffered that transcended

the rules of the ancient world. His compassion for the poor and the

sick led to institutions for lepers, the beginning of modern-day

hospitals. The Council of Nyssa decreed that wherever a cathedral

existed, there must be a hospice, a place of caring for the sick and

poor. That's why even today, hospitals have names like "Good Samaritan,"

"Good Shepherd," or "Saint Anthony." They were the world's first

voluntary, charitable institutions.

Humility

The ancient world honored many virtues like courage and wisdom, but

not humility. People were generally divided into first class and coach.

"Rank must be preserved," said Cicero; each of the original 99 percent

was a personis mediocribus. Plutarch wrote a self-help book that might

crack best-seller lists in our day: How to Praise Yourself

Inoffensively.

Jesus' life as a foot-washing servant would eventually lead to the

adoption of humility as a widely admired virtue. Historian John Dickson

writes, "it is unlikely that any of us would aspire to this virtue were

it not for the historical impact of his crucifixion...Our culture

remains cruciform long after it stopped being Christian."

Forgiveness

In the ancient world, virtue meant rewarding your friends and

punishing your enemies. Conan the Barbarian was actually paraphrasing

Ghengis Khan in his famous answer to the question "what is best in

life?" -- To crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and hear

the lamentations of their women.

An alternative idea came from Galilee: what is best in life is to

love your enemies, and see them reconciled to you. Hannah Arendt, the

first woman appointed to a full professorship at Princeton, claimed,

"the discoverer of the role of forgiveness in the realm of human affairs

was Jesus of Nazareth." This may be debatable, but he certainly gave

the idea unique publicity.

Humanitarian Reform:

Jesus had a way of championing the excluded that was often downright

irritating to those in power. His inclusion of women led to a community

to which women flocked in disproportionate numbers. Slaves--up to a

third of ancient populations--might wander into a church fellowship and

have a slave-owner wash their feet rather than beat them. One ancient

text instructed bishops to not interrupt worship to greet a wealthy

attender, but to sit on the floor to welcome the poor. The apostle Paul

said: "Now there is neither Jew nor Gentile, slave or free, male and

female, but all are one in Christ Jesus." Thomas Cahill wrote that this

was the first statement of egalitarianism in human literature.

There are all kinds of problems with these kinds of sweeping generalizations. But the fact that these changes in Western culture spring from religion, not science, is undeniable. I'm not sure science

per se has anything to say about humanitarianism, forgiveness, humility, how to treat children as human beings, or even the value of education, beyond the value of understanding science.

And on that point, does anyone else feel like they're listening to the Catholics and the Lutherans argue over the substance of the host in the Eucharist when they listen to climatologists arguing with meteorologists arguing with physicists about exactly what "global warming" means? This morning alone a scientist on

Diane Rehm assured me climate change is real, but at the same time we're insufficiently skeptical about what is real about it, and we really shouldn't do anything about it until we can be less skeptical (and he left me skeptical about his facts, since the journalist on the program corrected him on a few of the non-science ones, such as what treaties President Obama has signed). Immediately after on

Fresh Air a member of climate central assured me global warming is both real and must be responded to. Now certainly reasonable people can reasonably disagree, but the technicalities of the discussions are all concerned with the consequences of which particular shading you give to which particular interpretation of a set of facts which are themselves not established (one argument against climate change is that the data from reporting stations is inconsistent. No, seriously); and all the while Al Gore assures me that Rome is burning.

Is this really fundamentally different from quibbling over the number of angels that can dance on the head of a pin? Perhaps in theory it is; but in practice, we're still quibbling. What has changed here? That we're discussing climate models v. weather models, rather than sizes of pins and degrees of angelhood (and, to be fair, this was never an argument of the medieval church; the Renaissance made up that cliche as a jape against the medievalists. Of course, much of what obsessed the Renaissance would seem farcical to us now, too; also; as well. Anyway.....)

But you see, science is sciencey, and even the arguments over what are really fundamentals (do we do nothing? do we do something? It was said on Diane Rehm this morning that if we had done something 10 years ago, it would have been the wrong thing, because we were interpreting the wrong data in the wrong way, and it was better to have done nothing? As the pragmatists taught us a century ago, not to act is to act. Whither now?) are not considered arguments over fundamentals because we all agree that science=truth! Well, at least the truth that will solve all our problems and keep the

affluent society....affluent. (Honestly, when we're arguing about climate change, what else are we arguing about?)

Do I mean that religion has an answer to this problem, a solution that will resolve all? No. It's just interesting that religion is completely excluded from any consideration, except as to how religion causes problems, which, of course, science never does. Or if it does, well, bitter with the sweet and all. The science that gave us weapons of mass destruction and assault rifles and bombers, also gave us penicillin and air conditioning and skyscrapers, so whaddya want, eggs in your beer? And religion, on the other hand, makes people wear turbans and other people shoot them for wearing turbans, and is the cause of all the strife in the Middle East (funny how nothing else is the cause of that strife), and anyway more people died in religious wars than any wars evah, as any fule kno.

Or something.

People today decry the ignorance of science that leads to claims for "creationism" and calls for teaching something other than the Darwinian theory of evolution in biology. But ignorance of religion leads to the same end (creationism is born of ignorance in both realms), and religion is a more enduring aspect of human culture (and probably human nature) than science. Indeed, as much as there is clearly a "language instinct," I think there is a "religion instinct." The old 19th century model of "progress" whereby we will all advance beyond "superstition" and "belief" is belied by the very language used in the climate change debate. I didn't hear one scientist or hard-nosed journalist this morning who didn't speak in terms of belief in the data about climate change, as if the

sine qua non of scientific reasoning was to believe the data, and so finally to come to the true conclusion as to the state of reality; or at least, of the world's climate.

And anyone who wants to tell me "belief" in that context is completely and utterly different from "belief" in the context of religion, is going to immediately mark themselves as ignorant of the fundamentals of both fields, and of the proper use of langauge. Especially if you want to equate "belief" with "faith," and then say you "trust" the data of science (whatever data and whatever science. And one of the debates in the climate change argument is over what set of data to trust.), because "faith" means very little more than "trust."

Which is so unreasoning when it is applied to things traditionally religious, and so reasonable when applied to things traditionally scientific. But the fundamental dichotomy between them really doesn't stand up to scrutiny: you accept one, and not the other, because you trust one, and not the other. And at that point you're dealing with the "live option" that William James wrote about, not with what is "true" and what is "false." Because if you still believe in "true" and "false" in that simplistic way, I'll introduce you to the David Hume, the greatest of the empiricists. And I'll leave you there to figure your way to Kant and modernity; if you can.

I'm not making a truly cohesive argument here so much as jabbing argument against ignorance, and there is a great deal of that in the world. Why do you trust science, and distrust religion? Because you have learned science from the first grade, and learned religion, if at all, at home or in "Sunday school." You haven't, in other words, learned religion at all to the degree you've learned science. Which, in part, takes us back to the opening quote from Crooked Timber: there's a damned good reason we don't teach religion as we do science, because: MORMONS! Or some other such nonsense. The reason we don't teach religion is that, on the surface, there is so much disagreement between religions. But, as is apparent, while on the surface there is so much agreement between sciences, in reality, there is nothing but disagreement. The physicist who thinks the climatologist is misinterpreting the data and the meteorologist who sees a snake where the climatologist tries to see an elephant, are all arguing over basic understandings. Why isn't this seen as schismatic, rather than simply bewildering? (and don't even get me started on what physicists think of psychiatrists or anthropologists!). Perhaps because we teach religion as specific (and so don't teach it at all), while we teach science as general (and so miss the problems of the specific entirely, and don't know what to do with them when they arise.).

Should we teach religion in schools? Yes, but no more specifically than we teach science. We teach students who don't specialize in college "science." Not physics, or biology, or psychology, or anthropology, or chemistry...although we may teach any and all of those subjects. But chemists don't come from American high schools, nor physicists, nor meteorologists. We teach, in other words, the general tenets of science, the general principles of science, as they apply to living things, to rocks, to weather, to physical things. What if we taught, as religion, the basic tenets of religion. Things like, oh, I don't know: humility; compassion; education; humanitarianism. These could be taught as values in themselves, and as values arising from religions beliefs. Perhaps we could even teach religious tolerance, instead of a new version of religious intolerance championed by the "new atheists." We could teach it by teaching religion as a thing worth understanding, just as science and mathematics are worth understanding. Worth understanding even if you'll never be a scientist and don't really need to know how your computer works or why a phone rings or what keeps the food in your refrigerator cold. For all of those I know the basic principles; but if I can't identify them according to the basic laws of physics, or in terms of electrical theory, am I any the poorer for it? I always understood I was taught those basic principles not so I could design an internal combustion engine from the ground up, or replicate the telephonic communication system or even design a laptop from scratch, but just so I could understand. I know basically why a light bulb gives off light, but do I need to understand it as an engineer does, or a physicist? No more do I need to be devotee or even a priest in a religion, to understand something more basic to human existence than modern technology.

Being ignorant of it really hasn't done the world a great deal of good, and arguably has contributed to the rise of religions fundamentalism and religious fanaticism. Nature abhors a vacuum, and in the vacuum created by our modern ignorance of religion a whole host of demons has found refuge. Maybe, instead of cursing the darkness, we could start lighting a few more candles?