As of about now, it's 35° out in Katy, just a few miles west of me. Houston Airport is reporting 42°.

Winter is icummen in,

Lhude sing Goddamm!

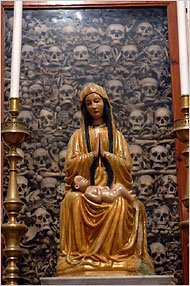

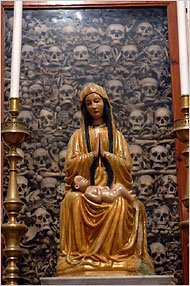

"I would like to say 'This book is written to the glory of God', but nowadays this would be the trick of a cheat, i.e., it would not be correctly understood."--Ludwig Wittgenstein

"OH JESUS OH WHAT THE FUCK OH WHAT IS THIS H.P. LOVECRAFT SHIT OH THERE IS NO GOD I DID NOT SIGN UP FOR THIS—Popehat

Winter is icummen in,

Lhude sing Goddamm!

"The spirit of the Lord is upon me,Israel was under occupation when those words were said. They were under occupation again when Jesus read them in the synagogue. And all he did, and all Isaiah did, was proclaim the rule of the law of Moses, proclaim that Israel would again be sovereign and conduct its own affairs. Or course, Jesus' claim was for the kingdom of God, not the kingdom of David. Still, the oppression of Israel was by an outside force.

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to announce pardons for prisoners

and recovery of sight to the blind;

to set free the oppressed,

to proclaim the year of the Lord's amnesty.

After rolling up the scroll, he gave it back to the attendant, and sat down; and the attention of everyone in the synagogue was rivted on him.

He began by saying to them, "Today, this scripture has come true as you listen."--Luke 4:18-21 (SV)

A record 7 million people — or one in every 32 American adults — were behind bars, on probation or on parole by the end of last year, according to the Justice Department. Of those, 2.2 million were in prison or jail, an increase of 2.7 percent over the previous year, according to a report released Wednesday.If an occupying force were levying this level of incarceration on the US, it would be a cause of the most violent turmoil, and who could disagree? One problem with being the sovereign in a democracy is that the people diffuse responsibility so greatly that there is no responsibility any more. We truly come to believe we do not jail our fellow citizens; they jail themselves. But when the number jailed rises to

More than 4.1 million people were on probation and 784,208 were on parole at the end of 2005. Prison releases are increasing, but admissions are increasing more.

Men still far outnumber women in prisons and jails, but the female population is growing faster. Over the past year, the female population in state or federal prison increased 2.6 percent while the number of male inmates rose 1.9 percent. By year's end, 7 percent of all inmates were women. The gender figures do not include inmates in local jails.

Arise, shine, Jerusalem, for your light has come;Matthew drew his wise men and their gifts from Isaiah's prophecy. It is part and parcel of the adventus that is again coming. And what does this new dawn herald? Good news to the humble, liberty to the captives, release to those in prison. Isaiah 61, in other words; the words read by Jesus, in Luke's gospel. It is all of a piece, if you put the pieces together. And yet we still prefer the assurances of our own power. And one in 7 of our fellow citizens, has known prison, or is on parole. The people who dwell in darkness have yet to see the promised light.

and over you the glory of the Lord has dawned.

Though darkness covers the earth and dark night the nations,

on you the Lord shines and over you his glory will appear;

nations will journey towards your light and kings to your radiance.

Raise your eyes and look around:

they are all assembling, flocking back to you;

your sons are coming from afar,

your daughters are walking beside them.

You will see it, and be radiant with joy,

and your heart will thrill with gladness;

sea-borne riches will be lavished on you

and the wealth of nations will be yours.

Camels in droves will cover the land,

young camels from Midian and Ephah,

all coming from Sheba

laden with gold and frankincense,

heralds of the Lord's praise.--Isaiah 60:1-6, REB

As we consider the alternatives for addressing crime and for responding humanly to both offenders and the victims of crime, we are reminded that, biblically understood, "criminal justice" is not a separate "issue" to be addressed by some political forum. The Bible does not instruct us to segregate our lives into areas defined by the issue of crime and the issue of poverty and the issue of morality and the issue of war and peace. Biblically understood, lawlessness and the prison are both manifestations not of a political issue but of a spiritual crisis that affects us all. It is a crisis wherein we persist in choosing death even though God has chosen life on our behalf. When we focus on this spiritual crisis, we see that violence and disrespect for life are the same no matter what the manifestation. And so we cannot talk about robbery on the streets of our cities without also talking about the robbery that takes place when we eat from full tables while one-third of the world remains malnourished. We cannot talk about violence on the streets of our cities without seeing its direct link to the fact that, as a nation, we are armedSee? An Advent lesson wherever you look.

to the teeth with enough nuclear weapons to obliterate our planet. If we talk about immorality and prostitution, we must do so with an eye to the numerous ways in which we prostitute ourselves to the gods of success, respectability, and material possessions. And so efforts to address the problem of crime nonviolently will necessarily involve us in efforts to feed the hungry, resist militarism, and climb on down the social ladder.

Will any of these alternatives work? We don't know. We have no guarantees. We only have the biblical story. But what a story it is, and what things we are told! And try as we might, we can't change the story. Try as we might to pin the labels on other people - criminal, thief, murderer, monster - that won't change the story that we all have one Creator and we are all sisters and brothers. We can spend the rest of our lives inventing new handcuffs and building new prisons, but that won't change the fact that Jesus proclaims liberty for the captives and the prisons have fallen. We can buy guns and stockpile nuclear weapons until the earth sinks under their weight, but nothing we can do will ever undo the resurrection and the fact that life is chosen for us. And we can call the police as often as we wish, but let us remember the story: Jesus comes as a thief in the night.--Lee Griffith, The Fall of the Prison: Biblical Perspectives on Prison Abolition (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans 1993), pp. 227-28.

[T]here are now more peace symbols in Pagosa Springs, a town of 1,700 people 200 miles southwest of Denver, than probably ever in its history.And the fine of $25 a day? Gone. Along with the 3 member board, who have all resigned. Two have disconnected their telephones. Seems there wasn't much support for their position, anywhere.

On Tuesday morning, 20 people marched through the center carrying peace signs and then stomped a giant peace sign in the snow perhaps 300 feet across on a soccer field, where it could be easily seen.

“There’s quite a few now in our subdivision in a show of support,” Mr. Trimarco said.

A former president of the Loma Linda community, where Mr. Trimarco lives, said Tuesday that he had stepped in to help form an interim homeowners’ association.

The former president, Farrell C. Trask, described himself in a telephone interview as a military veteran who would fight for anyone’s right to free speech, peace symbols included.

Town Manager Mark Garcia said Pagosa Springs was building its own peace wreath, too. Mr. Garcia said it would be finished by late Tuesday and installed on a bell tower in the center of town.

It's the birthday of William Blake, born in London (1757). He wrote Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794) and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790). He lived in poverty, ignorant of the rest of the literary world of London, scraping out a living from his trade as an engraver, and writing and drawing under inspiration he considered divine. He said about his long poem Milton, "I have written this poem from immediate dictation, twelve or sometimes twenty lines at a time, without pre-meditation and even against my will." He lived in a world of dreams and visions. One day he and his wife were sitting naked in their garden, reciting to each other passages from Paradise Lost. Blake was not embarrassed when a visitor came by. He said, "Come in! It's only Adam and Eve, you know."

"How should we then live" is the question everyone is chasing. The problem is, no one is considering how people live, when pursuing the question. How people ought to live is of great concern to a great number of people who never consider the conclusions should apply to them. How we ought to live is the province of the Big Idea, the one that always applies to thee, but never quite to me. How we should live is the province of parable and quotidian mystery, and turns me to thinking about my life and what I am doing. How conservatives ought to behave is of great concern to Mr. Bramwell; even how they ought to be punished. On this, he understands quite rightly that anyone's reach in that matter, will necessarily exceed their grasp; and that's not what a heaven's for:And I can only take responsibility, ultimately, for what I do to, or for, individuals. Grand ideas, more and more, feel like they are for me, by which I mean for my ego. Ideas guide my actions; but that's what they are for. The only legitimate control is over myself.

Worse, no reckoning will be made: they hope in vain who expect conservatives to take responsibility for the actual consequences of their actions. Conservatives have no use for the ethic of responsibility; they seek only to “see to it that the flame of pure intention is not quelched.” The movement remains a fine place to make a career, but for wisdom one must look elsewhere.

Religion, after all, is responsibility; or it is nothing at all. And religion is about the quotidian, and our daily responsibilities there. At least, that's part of my understanding of Christianity, and the gospel message.

I do get it: It's not wrong to want the best. But it is selfish and small and downright immoral to allow your wanting the best to put others in danger when you know your delusions are just that. You have the right to pretend. You don't have the right to ask someone to die for your puppet show. You don't have the right to keep thinking it'll get better, not when you know it won't.It's never even this simple. "It's not wrong to want the best." Except when "the best" means what's best for me, at the expense of you. And when does that not happen, except in a situation of absolute humility, engaged in by...me? This is precisely why Jesus taught that in the kingdom of heaven, the first are last and the last first. This is precisely why Christianity is supposed to preach a "race to the bottom" where we all struggle, not to exert power over one another in the name of peace or freedom or even God, but to be servants to each other. Servants don't have time to think about grand theories and large systems that if just finally and perfectly established, will guarantee peace for everyone everywhere for ever and ever, Amen. Servants just know they have to serve others. That is as much as they can do, and as much as they need to do. Blessed are the meek; they shall inherit the earth.

A homeowners association in southwestern Colorado has threatened to fine a resident $25 a day until she removes a Christmas wreath with a peace sign that some say is an anti-Iraq war protest or a symbol of Satan.I had a pair of sandals in high school with lateral leather straps. The broadest of the three held a peace sign, made out of leather also, bradded onto the cross strap. I still remember one night trying to convince the mother of a friend of mine that the symbol was not "Satanic."

Some residents who have complained have children serving in Iraq, said Bob Kearns, president of the Loma Linda Homeowners Association in Pagosa Springs. He said some residents have also believed it was a symbol of Satan. Three or four residents complained, he said.

"Somebody could put up signs that say drop bombs on Iraq. If you let one go up you have to let them all go up," he said in a telephone interview Sunday.

Lisa Jensen said she wasn't thinking of the war when she hung the wreath. She said, "Peace is way bigger than not being at war. This is a spiritual thing."

Jensen, a past association president, calculates the fines will cost her about $1,000, and doubts they will be able to make her pay. But she said she's not going to take it down until after Christmas.

With no obvious personal stake in the war in Iraq, most Americans are indifferent to its consequences. In an interview last week, Alex Racheotes, a 19-year-old history major at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, said: “I definitely don’t know anyone who would want to fight in Iraq. But beyond that, I get the feeling that most people at school don’t even think about the war. They’re more concerned with what grade they got on yesterday’s test.”Indeed, apocalypse and chaos are our sources of entertainment now.

His thoughts were echoed by other students, including John Cafarelli, a 19-year-old sophomore at the University of New Hampshire, who was asked if he had any friends who would be willing to join the Army. “No, definitely not,” he said. “None of my friends even really care about what’s going on in Iraq.”

This indifference is widespread. It enables most Americans to go about their daily lives completely unconcerned about the atrocities resulting from a war being waged in their name. While shoppers here are scrambling to put the perfect touch to their holidays with the purchase of a giant flat-screen TV or a PlayStation 3, the news out of Baghdad is of a society in the midst of a meltdown.

What's the central problem? It's still all about politics:

While such data may have been omitted to protect the group’s clandestine sources and methods — the document has a bold heading on the front page saying “secret,” and a warning that it is not to be shared with foreign governments — several security and intelligence consultants said in telephone interviews that the vagueness of the estimates reflected how little American intelligence agencies knew about the opaque and complex world of Iraq’s militant groups.

"They’re just guessing,” said W. Patrick Lang, a former chief of Middle East intelligence at the Defense Intelligence Agency, who now runs a security and intelligence consultancy. “They really have no idea.” He added, “They’ve been very unsuccessful in penetrating these organizations.”

“A judgment like that, coming from an N.S.C.-generated document,” is not an analytical assessment as much as it is a political statement to support the administration’s contention that Iraq is a central front in the war on terrorism, he said. “It’s a statement put in there to support a policy judgment.”Apparently that policy judgment is: we can't quit now. But what does the report say about Iraq?

The insurgency in Iraq is now self-sustaining financially, raising tens of millions of dollars a year from oil smuggling, kidnapping, counterfeiting, corrupt charities and other crimes that the Iraqi government and its American patrons have been largely unable to prevent, a classified United States government report has concluded.I suppose we can be grateful that at least the corrupt government officials aren't described as "men in Iraqi government uniforms."

The report, obtained by The New York Times, estimates that groups responsible for many of the insurgent and terrorist attacks are raising $70 million to $200 million a year from illegal activities. It says that $25 million to $100 million of the total comes from oil smuggling and other criminal activity involving the state-owned oil industry aided by “corrupt and complicit” Iraqi officials.

If Americans understood that soldiers were dying not to kill the bad guys but to prevent them from killing each other, Bush’s popularity would evaporate.We may be there soon:

Iraq's civil war worsened Friday as Shiite and Sunni Arabs engaged in retaliatory attacks after coordinated car bombings that killed more than 200 people in a Shiite neighborhood the day before. A main Shiite political faction threatened to quit the government, a move that probably would cause its collapse and plunge the nation deeper into disarray.The sad part is, one can almost consider that an improvement.

The massacre Thursday in Sadr City — a stronghold of Shiite Muslim cleric Muqtada Sadr and his Al Mahdi militia — sparked attacks around the country, reinforced doubts about the effectiveness of the Iraqi government and U.S. military and emboldened Shiite vigilantes.

In a sermon Friday, Sadr, a strong opponent of the United States, said the Pentagon's refusal to grant full control of Iraqi security forces to the Baghdad government was leaving the populace vulnerable to insurgent attacks.

With a timely reference to the rise and fall of the O.J. Simpson tell-some book (and what she's calls the "Thanksgiving Day Massacre" in Iraq) Maureen Dowd in her Saturday column for The New York Times suggests that President Bush go on Fox News and declare, "IF I did it -- here’s how the civil war in Iraq happened.”With the simple inevitability of winter coming 'round again, though. Sooner or later, this had to happen.

Bush, she writes, "could describe, hypothetically, a series of naïve, arrogant and self-defeating blunders, including his team’s failure to comprehend that in the Arab world, revenge and religious zealotry can be stronger compulsions than democracy and prosperity."

She also reveals that her own paper, along with other news outlets, "have been figuring out if it’s time to break with the administration’s use of euphemisms like 'sectarian conflict.' How long can you have an ever-descending descent without actually reaching the civil war?

"Some analysts are calling it genocide or clash of civilizations, arguing that civil war is too genteel a term for the butchery that is destroying a nation before our very eyes....

"It will be harder to sell Congress on the idea that America’s troops should be in the middle of somebody else’s civil war than to convince them that we need to hang tough in the so-called front line of the so-called war on terror against Al Qaeda."

“Defining Victory” [an editorial previously published in the National Review, which also published this essay] describes the post-9/11 world in terms that have since become familiar. First, it insists on a war that has no definite enemy and no foreseeable end. Short of one-world despotism or universal brotherhood, the U.S. cannot literally defeat “all those who mean to do our people harm.” To trim the hyperbole, NR goes on to name five examples of potential enemies (plus, in later editorials, Saudi Arabia) but does not explain how the list was generated or whether it is even complete. The reader gathers only that we should threaten or go to war with an unspecified number of troublesome nations.Who can argue with such clear-headedness, such clarity of insight? This is the problem with belligerence in a nutshell, or with war as "therapy," as Richard Cohen advocated. The only logical answer to that claim is a question: therapy for whom? But the conclusion of this catalogue is the best, indeed, the most unbelievable part:

Second, the editors use the term “war” in a purely figurative sense. At the time of the editorial, the U.S. was not at war with Syria, Sudan, or Iran nor, realistically speaking, with any other nation on the list. No matter how vulnerable or despised, no Muslim nation can be turned into a sacrificial substitute for bin Laden. Nor, no matter how often incanted, can the phrase “at war” be made to describe an actual state of affairs. A rhetorical bludgeon designed to compel assent to certain policies, it begs the question of whether war is advisable in the first place.

Third, “Defining Victory” does not identify a casus belli. Neither Iraq, Syria, Iran, Libya, nor Sudan attacked us on 9/11. Later debate would focus on the legitimacy of preventive war as a defense against future threats. All foreign nations, however, by definition pose hypothetical threats; at some point, those threats become so remote, trivial, or contingent that preventive war cannot be distinguished from an aggressive war of domination. By urging belligerence against nations with no known designs—to say nothing of any capacity—for harming the U.S., “Defining Victory” surely advocated crossing that point.

Finally, the editorial defines “victory” in terms of a goal—regime change—that war advances only incidentally. War by itself cannot cause regime change. To overthrow and replace a government militarily, one must either invade and occupy a country (a technique that works best when the occupier has made a policy of slaughtering civilians en masse, as in Dresden or Hiroshima) or else so punish the civilian population that they rise up against their government. By saying, incoherently, that the United States was “at war” with a list of regimes, NR gave no indication of what policies it was actually touting.Would have been nice if somebody had mentioned that before we attacked Iraq, huh?

As it happens, the broader conservative public supports Bush for very sensible, non-neoconservative reasons. Those reasons just happen to be poorly informed. For example, many believe—including an astonishing 90 percent of soldiers serving in Iraq—that the U.S. invaded to retaliate against Saddam Hussein for his role in the 9/11 attacks. Now that Saddam is gone but Iraqis are still giving us trouble, they reason, we must kill them before they kill us. If Americans understood that soldiers were dying not to kill the bad guys but to prevent them from killing each other, Bush’s popularity would evaporate.But it never quite makes the point that those soldiers who are dying are really human beings. Of course, that is what soldiers are for. Everybody knows that.

The Roman Empire was based on the common principle of peace through victory, or, more fully, on a faith in the sequence of piety, war, victory, and peace.In the end, Bramwell is merely making the argument of Rome: that peace comes through a faith in the sequence of piety (he mentions Christianity favorably, although I imagine he and I would quarrel on what "Christianity" means), war, victory, and peace. It's simply that he understands war, victory, and peace are slightly more complex matters than those he critiques think they are. But he certainly is not offering an alternative of peace through covenant, nonviolence, and justice. Indeed, he would clearly consider me (who agrees with Paul) a hopeless idealist, if not a Pollyanna.

Paul was a Jewish visionary following in Jesus' footsteps, and they both claimed that the Kingdom of God was already present and operative in this world. He opposed the mantras of Roman normalcy with a vision of peace through justice, or, more fully, with a faith in the sequence of covenant, nonviolence, justice, and peace.

The notion of a crisis of the West, however, grossly overestimates the importance of ideas; indeed, it requires an unphilosophical and almost paranoid ability to treat ideologies (most conspicuously, liberalism) as living, breathing omnipresences to which intentions, tactics, strategies, feelings, disappointments, and conflicts can all be attributed.Again, this is so clear-sighted and rational that I cannot argue with it. Indeed, one can make this same critique ring loudly true against left blogistan. But I don't need to argue with it; it is my point in a nutshell. Because this is as close as Bramwell gets to making any reference to real people, outside of the ideas they adopt and try to live by.

Still others eulogize local attachments and ancestral loyalties. They invoke a litany of examples: family, church, kin, community, school, the “little platoons” in which Burke found the basis of political association. Celebrating such “infra-political” institutions may well have made sense in the 1950s, the high tide of American nationalism and federal government prestige. At most other times, however, ancestral attachments are dangerously subversive. The U.S. could not have survived had it not ruthlessly extirpated the ancestral loyalties of both natives and newcomers; Great Britain suffered endless civil wars before the great constitutional oak that Burke praised took root; the West itself succeeded precisely because it cut short the reach of the extended family or clan. Ancestral loyalties are the curse of uncivilized peoples, most especially in the hypermnesiac Middle East. Most ominously, praise of local attachments now comes in the guise of multiculturalism, perhaps the most insidious threat to a just order today. Not for nothing did communitarianism become a left-wing vogue.Certainly Jesus makes much the same argument (I have come to set son against father, daughter against mother), but Jesus was talking about devotion to God above all else, not 19th century notions of nationalism (which Bramwell seems to take as some kind of Platonic ideal of human organization, rather than a result of the peculiarities of European history). Bramwell is positively Roman in his outlook: all local and even familial concerns, must be viewed through the lens of empire, else civilization itself fails. Again, everything must be subsumed into service to the Big Idea. But ideas are not human beings; ideas are not alive, do not draw breath, do not have legs and hearts and lungs; ideas do not even die. In precisely that much "V" was right: ideas are bulletproof. But that's because ideas aren't alive. AS Jesus said: God clothes the flowers of the field and feeds the birds of the air; surely God will take care of you, too. Not your ideas, or even your ideals: simply you. Ideas are not more important than people. Surely if his teachings were about anything, they were about that.

Worse, no reckoning will be made: they hope in vain who expect conservatives to take responsibility for the actual consequences of their actions. Conservatives have no use for the ethic of responsibility; they seek only to “see to it that the flame of pure intention is not quelched.” The movement remains a fine place to make a career, but for wisdom one must look elsewhere.Religion, after all, is responsibility; or it is nothing at all. And religion is about the quotidian, and our daily responsibilities there. At least, that's part of my understanding of Christianity, and the gospel message.

The treatment of his war minister connotes something deeply wrong with George W. Bush's presidency in its sixth year. Apart from Rumsfeld's failures in personal relations, he never has been anything short of loyal in executing the president's wishes. But loyalty appears to be a one-way street for Bush. His shrouded decision to sack Rumsfeld after declaring that he would serve out the second term fits the pattern of a president who is secretive and impersonal.The news this morning:

Two bombs killed 22 people in northern Iraq on Friday as the government tried to tamp down violence and head off civil war a day after Sunni-Arab insurgents killed 215 people in an attack on Baghdad's Sadr City slum that intensified Shiite anger at the United States.Which of these events "connotes something deeply wrong with George W. Bush's presidency in its sixth year"?

The blasts in Tal Afar, 260 miles northwest of Baghdad, involved explosives hidden in a parked car and in a suicide belt worn by a pedestrian that detonated simultaneously outside a car dealership at 11 a.m., said police Brig. Khalaf al-Jubouri. He said the casualties — 22 dead, 26 wounded — were expected to rise.

Pope Benedict XVI's envoy to the United States to bring aid for Hurricane Katrina's victims said Saturday that many of them have been struck by "shameful" poverty in "rich America."In that same post, I notede that the President had pledged to provide "whatever it costs" to rebuild the Gulf Coast.

...

"The weakness experienced by the United States faced with this catastrophe" serves to "destroy all of our beliefs about self-sufficiency," the Vatican official said. "Thus, for me, in the bad part of this event there is also the hope, for many citizens, of seeing that the world is greater than the United States," Cordes said.

The covenental kingdom's sublime perfection is the eschatological or eutopian kingdom and the eschatological kingdom's imminent advent is the apocalyptic kingdom. They are on a continuum from ideal good (covenant) to perfect best (eschatology) and from distant hope (eschatology) to proximate presence (apocalypse). The further the present kingdom of God deviated from normal good, teh more some people looked to ideal best. The further that ideal deviated from present now, the more some poeple looked to future soon. An apocalypse is a "revelation" about that "ending" of evil and injustuce as coming soon, very soon, right now almost. Without some continuity from covenantal to eschatological Kingdom of God, the content of an apocalyptic kingdom becomes an open question or an empty expectation.--John Dominic Crossan and Jonathan L. Reed, Excavating Jesus (New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2001) p. 115.

At that time Michael, the great prince, the protector of your people, shall arise. There shall be a time of anguish, such as has never occurred since nations first came into existence. But at that time your people shall be delivered, everyone who is found written in the book. Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt. Those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky, and those who lead many to righteousness, like the stars forever and ever.Hebrews 10:11-14, (15-18), 19-25

And every priest stands day after day at his service, offering again and again the same sacrifices that can never take away sins. But when Christ had offered for all time a single sacrifice for sins, "he sat down at the right hand of God," and since then has been waiting "until his enemies would be made a footstool for his feet."Mark 13:1-8

For by a single offering he has perfected for all time those who are sanctified. And the Holy Spirit also testifies to us, for after saying, "This is the covenant that I will make with them after those days, says the Lord: I will put my laws in their hearts, and I will write them on their minds," he also adds, "I will remember their sins and their lawless deeds no more." Where there is forgiveness of these, there is no longer any offering for sin. Therefore, my friends, since we have confidence to enter the sanctuary by the blood of Jesus, by the new and living way that he opened for us through the curtain (that is, through his flesh), and since we have a great priest over the house of God, let us approach with a true heart in full assurance of faith, with our hearts sprinkled clean from an evil conscience and our bodies washed with pure water. Let us hold fast to the confession of our hope without wavering, for he who has promised is faithful. And let us consider how to provoke one another to love and good deeds, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day approaching.

As he came out of the temple, one of his disciples said to him, "Look, Teacher, what large stones and what large buildings!" Then Jesus asked him, "Do you see these great buildings? Not one stone will be left here upon another; all will be thrown down." When he was sitting on the Mount of Olives opposite the temple, Peter, James, John, and Andrew asked him privately, "Tell us, when will this be, and what will be the sign that all these things are about to be accomplished?" Then Jesus began to say to them, "Beware that no one leads you astray. Many will come in my name and say, 'I am he!' and they will lead many astray. When you hear of wars and rumors of wars, do not be alarmed; this must take place, but the end is still to come. For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom; there will be earthquakes in various places; there will be famines. This is but the beginning of the birthpangs.Not that it mattered, to be perfectly honest: most of the family there were clearly unfamiliar with church, and treated it as a public theater: i.e., a place to stand about and talk until the lights dim and you hasten to take your seats to watch the show. Most of them displayed no sense of the behaviour expected in an Episcopal setting, and stood up to leave as soon as the priest had walked out (we regulars know to wait for the dousing of the candles. It was conducted that Sunday in something of a scrum as the "audience" resumed their conversations interrupted by the start of the "show"). So these words didn't mean much to them; just more of what "church is about," and another reason why they don't usually attend (it's not always due to pomp and circumstance, in other words).

When you hear of wars and rumors of wars, do not be alarmed; this must take place, but the end is still to come. For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom; there will be earthquakes in various places; there will be famines. This is but the beginning of the birthpangs.Condi Rice used this language to justify the war in Iraq; but that is arrogance and ignorance speaking. Jesus doesn't tell us to be in charge of events; he says events will seem to be in charge of us. The will-to-power of the evangelical leaders, of any person who thinks they can shape the zeitgeist, is not given a how-to manual here. This is something altogether different. Daniel echoes it, too:

There shall be a time of anguish, such as has never occurred since nations first came into existence. But at that time your people shall be delivered, everyone who is found written in the book. Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt. Those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky, and those who lead many to righteousness, like the stars forever and ever.These are words of hope, but they are a realistic hope. Daniel doesn't promise exemption, he promises justice. "Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth...Those who are wise." Justice restores, justice doesn't protect. Justice breaks the cycle of the calendar. Justice is the gift. And its coming is heralded by wars and kingdoms rising against kingdoms, and earthquakes in various places, and famine; and those are just the birthpangs. Imagine what the rest is like. This is not the gift anyone expects, or can expect. We expect power to bring peace, war to bring justice, destruction to bring consent. We expect fighting to lead to victory, and victory to pax. Whenever we seek peace by our own means, by the exertion of our own power, we seek pax, but not shalom. Pax is the peace enforced by power; shalom is the peace of God, which passes all understanding. Shalom is the gift that breaks the cycle of exchange. Shalom is the gift which cannot be foreseen, cannot even be received. It truly comes in spite of us, and apart from us, and yet it is given to us, or it isn't a gift at all.

And let us consider how to provoke one another to love and good deeds, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day approaching.The gift that shatters the cycle of time is coming. The gift we least expected and never expect again, is being repeated. The season that opens our eyes to that gift is coming around again, ever the same, ever new again. Paradoxes abound; so does confusion. Blessed are those who don't even know it has come, for they shall be the first to receive it.

"My son is an honest man," Bush told members of the audience harshly criticized the current U.S. leader's foreign policy.I'm tempted to dismiss this as Bush's "I am not a crook" moment. I'm not sure criticism of foreign policy is the equivalent of saying the President is dishonest. He may be perfectly honest in his opinions about Iraq. That doesn't make him right, however; nor does it foreclose explanations based on greed.

"We do not respect your son. We do not respect what he's doing all over the world," a woman in the audience bluntly told Bush after his speech.

Bush, 82, appeared stunned as others in the audience whooped and whistled in approval.

A college student told Bush his belief that U.S. wars were aimed at opening markets for American companies and said globalization was contrived for America's benefit at the expense of the rest of the world. Bush was having none of it.

"I think that's weird and it's nuts," Bush said. "To suggest that everything we do is because we're hungry for money, I think that's crazy. I think you need to go back to school."

The hostile comments came during a quesion-and-answer session after Bush finished a folksy address on leadership by telling the audience how deeply hurt he feels when his presidential son is criticized.

"This son is not going to back away," Bush said, his voice quivering. "He's not going to change his view because some poll says this or some poll says that, or some heartfelt comments from the lady who feels deeply in her heart about something. You can't be president of the United States and conduct yourself if you're going to cut and run. This is going to work out in Iraq. I understand the anxiety. It's not easy."

"He is working hard for peace. It takes a lot of guts to get up and tell a father about his son in those terms when I just told you the thing that matters in my heart is my family," he said. "How come everybody wants to come to the United States if the United States is so bad?"Guts? Well, maybe. But especially when speaking directly to the people most affected by the President's "honesty," that statement has the ring of the soldier's line about Patton, 'Ol' Blood 'n' Guts:' "Our blood, his guts." I'm not sure these people were courageous so much as honest; a quality usually admired in the abstract, and derided in the concrete.

Most troubling, he said, are his shattered ideals: "The whole philosophy of using American strength for good in the world, for a foreign policy that is really value-based instead of balanced-power-based, I don't think is disproven by Iraq. But it's certainly discredited."Actually, what is most troubling is the rise of the mega-church and the "feel good" branch of Christianity, and the idea that God is on our side, and that we can usher in the kingdom of heaven and bring about the millennia if we help Israel, or otherwise engage in the "right" foreign policy.

The Democratic victories this month led to a surge of calls for the Administration to begin direct talks with Iran, in part to get its help in settling the conflict in Iraq. British Prime Minister Tony Blair broke ranks with President Bush after the election and declared that Iran should be offered “a clear strategic choice” that could include a “new partnership” with the West. But many in the White House and the Pentagon insist that getting tough with Iran is the only way to salvage Iraq. “It’s a classic case of ‘failure forward,’” a Pentagon consultant said. “They believe that by tipping over Iran they would recover their losses in Iraq—like doubling your bet. It would be an attempt to revive the concept of spreading democracy in the Middle East by creating one new model state.”Double down, indeed.

The view that there is a nexus between Iran and Iraq has been endorsed by Condoleezza Rice, who said last month that Iran “does need to understand that it is not going to improve its own situation by stirring instability in Iraq,” and by the President, who said, in August, that “Iran is backing armed groups in the hope of stopping democracy from taking hold” in Iraq. The government consultant told me, “More and more people see the weakening of Iran as the only way to save Iraq.”

The consultant added that, for some advocates of military action, “the goal in Iran is not regime change but a strike that will send a signal that America still can accomplish its goals. Even if it does not destroy Iran’s nuclear network, there are many who think that thirty-six hours of bombing is the only way to remind the Iranians of the very high cost of going forward with the bomb—and of supporting Moqtada al-Sadr and his pro-Iran element in Iraq.” (Sadr, who commands a Shiite militia, has religious ties to Iran.)

In the current issue of Foreign Policy, Joshua Muravchik, a prominent neoconservative, argued that the Administration had little choice. “Make no mistake: President Bush will need to bomb Iran’s nuclear facilities before leaving office,” he wrote. The President would be bitterly criticized for a preëmptive attack on Iran, Muravchik said, and so neoconservatives “need to pave the way intellectually now and be prepared to defend the action when it comes.”

The main Middle East expert on the Vice-President’s staff is David Wurmser, a neoconservative who was a strident advocate for the invasion of Iraq and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. Like many in Washington, Wurmser “believes that, so far, there’s been no price tag on Iran for its nuclear efforts and for its continuing agitation and intervention inside Iraq,” the consultant said. But, unlike those in the Administration who are calling for limited strikes, Wurmser and others in Cheney’s office “want to end the regime,” the consultant said. “They argue that there can be no settlement of the Iraq war without regime change in Iran.”

For 11 months, Bashmilah was held in one of the CIA's most secret prisons - its so-called "black sites" - so secret that he had no idea in which country, or even on which continent, he was being held. He was flown there, in chains and wearing a blindfold, from another jail in Afghanistan; his guards wore masks; and he was held in a 10ft by 13ft cell with two video cameras that watched his every move. He was shackled to the floor with a chain of 110 links.Because we've heard all this before; and we will hear it all again; and again, and again, and again.

From the times of evening prayer given to him by the guards, the cold winter temperatures, and the number of hours spent flying to this secret jail, he suspected that he was held somewhere in eastern Europe - but he could not be sure.

When he arrived at the prison, said Bashmilah, he was greeted by an interrogator with the words: "Welcome to your new home." He implied that Bashmilah would never be released. "I had gone there without any reason, without any proof, without any accusation," he said. His mental state collapsed and he went on hunger strike for ten days - until he was force-fed food through his nostrils. Finally released after months in detention without being charged with any crime, Bashmilah was one of the first prisoners to provide an inside account of the most secret part of the CIA's detention system.

On 6 September, President George W Bush finally confirmed the existence of secret CIA jails such as the one that held Bashmilah. He added something chilling - a declaration that there were now "no terrorists in the CIA programme", that the many prisoners held with Bashmilah were all gone. It was a statement that hinted at something very dark - that the United States has "disappeared" hundreds of prisoners to an uncertain fate.

Let's examine the arithmetic of this systematic disappearance. In the first years after the attacks of 11 September, thousands of Taliban or suspected terrorist suspects were captured. Just in Afghanistan, the US admitted processing more than 6,000 prisoners. Pakistan has said it handed over around 500 captives to the US; Iran said it sent 1,000 across the border to Afghanistan. Of all these, some were released and just over 700 ended up in Guantanamo, Cuba. But the simple act of subtraction shows that thousands are missing. More than five years after 9/11, where are they all? We know that many were rendered to foreign jails, both by the CIA and directly by the US military. But how many precisely? The answer is still classified. No audit of the fate of all these souls has ever been published.

A German-born Turk, who was held for four years in the US detention camp at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, has alleged systematic torture in the hands of the US military, from beatings to being chained to a ceiling for days.Obviously I don't want to let that part pass by. It's something we've known, for some time now:

Murat Kurnaz, 24, who was released in August because of lack of evidence he was involved in terrorist activities, said he endured ”many types of torture -- from electric shocks to having one’s head submerged in water, (subjection to) hunger and thirst, or being shackled and suspended.”

[snip]

“They tell you “you are from Al Qaed”’ and when you say “no” they give the (electric) current to your feet.... As you keep saying ‘no’ this goes on for two or three hours,” he said, adding he had several times lost consciousness.

He claimed he was once shackled to a ceiling for “four or five days”.

“They take you down in the mornings when a doctor comes to see whether you can endure more,” he said. “They let you sit when the interrogator comes.... They take you down about three times a day so you do not die.”

Military doctors at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, have aided interrogators in conducting and refining coercive interrogations of detainees, including providing advice on how to increase stress levels and exploit fears, according to new, detailed accounts given by former interrogators.Although Dick Cheney insists otherwise:

The accounts, in interviews with The New York Times, come as mental health professionals are debating whether psychiatrists and psychologists at the prison camp have violated professional ethics codes. The Pentagon and mental health professionals have been examining the ethical issues involved.

Vice President Dick Cheney said on Thursday that prisoners at the detention camp in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, had everything they could possibly want and were well fed and well treated as they lived in the "tropics."Still, the evidence of abuse continues to mount. The early questions were of experiments, reminiscent of those conducted by the Nazis. When it became clear that was true, the next question was: is it ethical for medical professionals to aid in the torture of prisoners? And the answer, of course, is: No.

For those in positions of public trust, that they may serve justice, and promote the dignity and freedom of every person, we pray to you, O Lord.

But one must not think ill of the paradox, for the paradox is the passion of thought, and the thinker without the paradox is like the lover without passion: a mediocre fellow. But the ultimate potentiation of ever passion is always to will its own downfall, and so it is also the ultimate passion of the understanding to will the collision, in one way or another the collision must cause its downfall. This, then, is the ultimate paradox of thought: to want to discover something that thought itself cannot think.Johannes Climacus, Philosophical Fragments, ed. Soren Kierkegaard, tr. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1985), 37.