when reading something like this, is:

When Brad Pitt, as the astronaut Roy McBride, flies to the moon in James Gray’s elegant space epic Ad Astra, he takes Virgin Atlantic. Though the company’s logo looks roughly the same, an onboard blanket-and-pillow pack will, by the time this movie’s undated near-future arrives, cost $125. The moon base where Roy’s commercial flight lands also boasts an Applebee’s, a Subway, and other familiar fixtures of the landscape of 21st-century capitalism. These brand names go uncommented on, mere background details in the dense weave of a story that pairs intense action sequences—we’ll get to the moon-buggy car chase momentarily—with long stretches of near silent cockpit-bound solitude. But the inclusion of those familiar corporate signs gives this sometimes driftingly abstract movie a grounding in the recognizable world, not to mention a welcome dash of humor.

Is the reviewer too young to remember "2001" (which this movie, from the description, clearly echoes)? Or too young to know that PanAm (the space shuttle to the space station), and Hilton and Bell Telephone (all make an appearance at the space station) were real companies then (not so much by 2001)?

Although I must admit this paragraph:

Many of the auteur-driven space exploration sagas of the past decade–Gravity, First Man, Interstellar, The Martian—have focused on the loneliness of the individual astronaut, cut off from all earthly sources of comfort and meaning and forced to reinvent life from the ground up in a place where there is no ground; where in moral as well as gravitational terms, up is down and down is up. Ryan Gosling’s existentially adrift Neil Armstrong, Sandra Bullock’s solitary survivor of a space station–destroying disaster, Matt Damon’s left-behind scientist sowing his potatoes in the red Mars dirt: All these were movie stars-in-space in the same tradition as Pitt’s Roy McBride, who also supplies a noir-tinged voiceover that’s reminiscent of the older sci-fi classic Blade Runner. The rarefied states of film celebrity and cosmic solitude somehow go naturally hand in hand. The hyper-recognizability of world-famous faces under those globe-shaped helmets is part of what makes their predicament so identifiable: If Brad Pitt can get lost in space, anyone can.

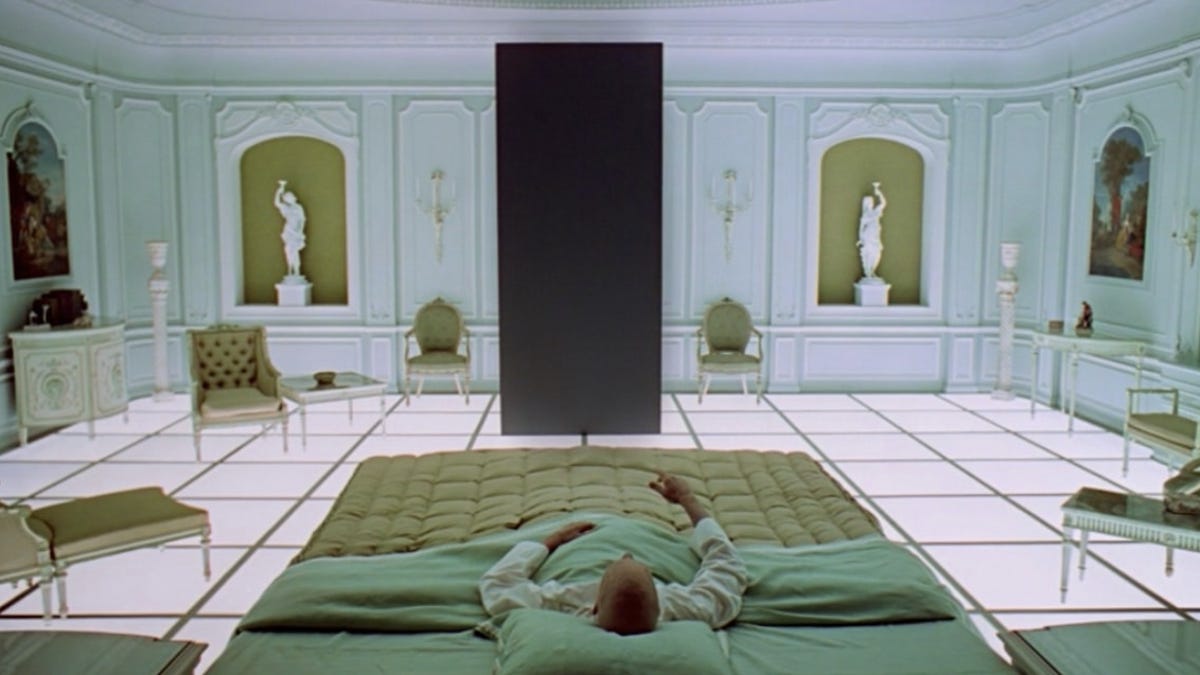

Makes me long for the non-introspective, no-interior life, of the astronauts in Kubrick's film. The common thread of all those films, as described there, is that "the trip outward is accompanied by an equal and opposite journey within." That lack of an interior journey is what marks Kubrick off from all the others, which is probably why his film gets no mention here.*

I hate getting old. But I do have a copy of Kubrick's film I can watch, and suddenly I fell compelled to.

*Which is an odd lacunae still, because this brief summary of the plot sounds a lot like an echo of the 1968 film:

The dad in question, H. Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones), is a legendary scientist and space explorer who disappeared decades ago on a mission so classified that Roy has to take the first leg of his Neptune-bound journey undercover. Donald Sutherland, as an old friend of Clifford now charged with serving as his son’s mentor, provides some sinuous exposition about the possible connection between the elder McBride’s fate and the errant energy bursts now endangering the solar system.

A secret mission? (Kubrick kept the reasons away from even the astronauts, until they reached Jupiter space). Mysterious energy transmissions from (or to) space? "Mind-bending cosmic spectacles"? (That's from later in the same paragraph). Check, check, and check; if there's a checklist, and there sure seems to be. Even the scene of Poole drifting in space, dead at the hands of a pod controlled by HAL, is in "Ad Astra" one of the many "long shots that emphasize the tininess of human beings and their creations amid the vast abyss of space." Or even this: "hinting at a melancholic truth that slowly reveals itself to the viewer (and even more slowly, to Roy): No matter how far away from Earth we travel, there’s no escaping our own human problems, limitations, and weaknesses," which is true for Kubrick's astronauts as well as for humanity's creation, the HAL 9000 computer. Or, more ironically, this:

The sickness of patriarchy, Ad Astra suggests, lies not only within individual men: It’s built into a system that values humans insofar as they can act and react like machines.

In the end, I admire the Kubrick film more just by comparison, especially as "Ad Astra," at least per this review, ends with the inward journey actually discovering something:

But the confrontation the movie builds toward, as Roy’s journey takes him ever closer to the father who’s spent a lifetime getting as far from humanity as possible, is the opposite of a superhero-style apotheosis. “I will not rely on anyone or anything,” Roy repeats to himself early in the movie, both as a personal mantra and a professional vow. “I will not be vulnerable to mistakes.” It’s the slow and painful abandonment of that cult of self-sufficiency that makes the final scenes so moving, and that brings the soaring abstractions of Ad Astra back down, beautifully, to earth.

Kubrick's ending looks better and better. At least to an old person like me.

No comments:

Post a Comment