And apropos of this post (and to introduce a few entries from another of Niebuhr's books):

We had a great Easter service today....We received our largest class of new members into the church thus far, twenty-one in all. Most of them had not letters from other churches and yet had been reared in some church. We received them on reaffirmation of faith.

This matter of recruiting a membership for the church is a real problem. Even the churches which once believed a very definite conversion experience to be the sine qua non of entrance into the fellowship of the church are going in for "decision days" as they lose confidence in the traditional assumption that one can become a Christian only through a crisis experience. But if one does not insist on that kind of experience it is not easy to set up tests of membership. Most of these "personal evangelism" campaigns mean little more than ordinary recruiting effort with church membership rather than Christian life as the real objective. They do not differ greatly from efforts of various clubs as they seek to expand their membership.

Of course we make "acceptance of Jesus as your savior" the real door into fellowship in the church. But the trouble is that may mean everything or nothing. I see no way of making the Christian fellowship unique by any series of tests which precede admission. The only possibility lies in a winnowing process through the instrumentality of the preaching and teaching function of the church. Let them come in without great difficulty, but make it difficult for them to stay in. The trouble with this plan is that is is always easy to load up membership with very immature Christians who will finally set the standard and make it impossible to preach and teach the gospel in its full implications.

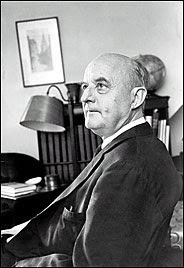

--Reinhold Niebuhr, "1919." Leaves from the Notebooks of a Tamed Cynic. Louisville, Kentucky: John Knox/Westminster Press, original publication date 1929. p. 23.

This is Reinhold Niebuhr, recording contemporaneously his experiences as a new pastor in Detroit at the beginning of the last century. It is the conclusion that makes the point: what is church for? For anyone, including non-believers? And how many of those can be allowed in before it is "impossible to preach and teach the gospel in its full implication"? Yet I have pastored churches where that was already impossible, and no one in that congregation would admit to being an atheist.

They were more likely to label me a heretic.

"Make it difficult for them to stay"? The only person who would find it difficult to stay in that church would be the pastor.

And I've held fast to the idea that church membership today means nothing more than the "efforts of various clubs as they seek to expand their membership." It makes me sound terribly cynical to out-Herod Herod on this point, but it is my experience nonetheless. I served two churches that insisted increasing membership was a necessary goal; but all they really meant was to make the club more popular, by enticing more people like them to appear on a more permanent basis. There is comfort in numbers, but greater comfort in people like us.

But for many churches, there are fewer and fewer such people around. Interestingly, in 1919 only about 41% of Americans considered themselves affiliated with any kind of religion. (I use this study constantly because I find context around these issues constantly important). So Niebuhr is contemplating an America even more different from our own, but not in the way we might imagine. Like the church today, Niebuhr had to work with, and accept into his church fellowship, the "unchurched." Believers, but believers who really don't want to be asked to do anything for the sake of their belief. Should they be winnowed later? Willow Creek Community Church uses that model, but studies have found it doesn't really lead to any greater commitment than to show up on Sunday morning for the show. Especially in the "seeker service" that was "a pretty good show for a buck."*

Robert Wuthnow makes much of something that never seems to occur to Niebuhr: the need for the church to raise the money it takes to continue being a church: building, programs, employees, etc. But is that what church is for? Upon re-reading his book I want to introduce him to Walt Kallestad:

Walt led Community Church of Joy in Phoenix, a megachurch that had been an average congregation of 200 before he took over in the 80s and oversaw it's growth. But in 2002 he suffered a massive heart attack requiring six-way bypass surgery. The heart attack, says Walt, was a "wake up call" for the leaders to develop a succession plan to ensure the megachurch continued to thrive after Walt's tenure.

Kallestad began networking around the country looking for a young pastor he could bring onboard and eventually hand the church over to. One conversation stuck with him.

"It's a pretty good opportunity," Walt said. "We have 187 acres just off a major freeway, multipurpose buildings, and a great staff."

The leader looked him in the eyes and said, "Who'd want it? Who in their right minds would want to run that?"

"That's when it dawned on me," Kallestad reflected. "By the time we service the $12-million debt, pay the staff, and maintain the property, we've spent more than a million before we can spend a dime on our mission. At the time, we had plans for a spectacular worship center with a retractable roof. After that conversation, I scrapped it."

Making those changes, by the way, cost Kallestad 4000 church members. I've never been even associated with a church with that many members, much less one that could lose that many and still exist as an institution. And maybe the lesson of the Crystal Cathedral is instructive here: when Schuller died, the church had to sell the building to the Catholic diocese just to pay its debts.*

So how do we make Christian fellowship unique?

*An old joke I picked up in seminary, about what it "costs" to attend worship on any given Sunday.

**I got carried away with this, but you can have my footnotes. I couldn't find any numbers on the membership of CCJ, a church I had some encounter with in seminary. According to Internet Monk, at it's height CCJ had 12,000 members. In 2009, when it broke with the ELCA over the ordination of gays and lesbians (CCJ was agin it), they reported 6800 members, an attendance of 2500. Where their membership is now is anybody's guess, but Internet Monk provides more information on how two megachurches decided "seeker services" weren't the alpha and omega of Christian discipleship. We always come back to the Church of Meaning and Belonging v. the Church of Sacrifice for Meaning and Belonging. And if I keep repeating all of this it's only because I long for a serious conversation on these topics, and the best I get is people misreading and misunderstanding the latest Pew polls. No, I don't mean to be haughty; but damn!, the signal to noise ratio on the internet is low!

No comments:

Post a Comment