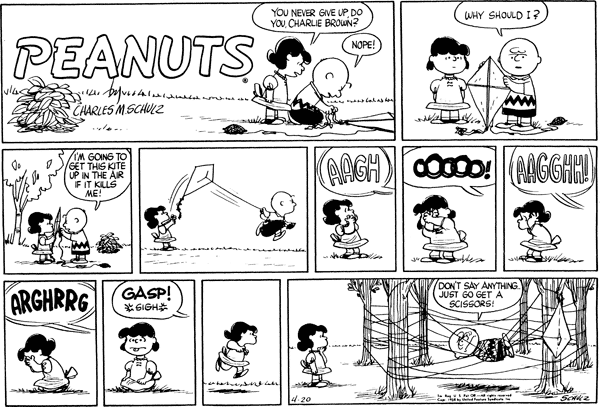

A fairly neat parable for most of my arguments....

I haven't seen "Wild, Wild Country" on Netflix because I don't think I really want to. But follow this argument (the conclusion of an article about the documentary) and see where it ends up:

So why can’t I look away from Sheela? Watching her gave me new insight into Trump’s attraction to his base: The over-the-top offensiveness is part of the charm. The actual Sheela lives in Switzerland today and quite plausibly gives not one whit about where she falls in the identitarian camps of America in 2018. But her social media–anointed drafting into the #Resistance makes sense, since her anger at “bigots” and “fascists” coincides with the left’s contemporary language. Her certitude and zeal also parallel the crudity of political discourse on both sides in the Trump era. After seeing that “we go high when they go low” doesn’t work, many liberals have been craving a honey badger of their own. That she’s seen in the current day in a neat gray bob, gold-rimmed glasses, and a grandmotherly shawl adds to her political appeal: We’re reasonable, everyday people until given a reason to Hulk out.Sheela didn't succeed because she committed criminal acts:

Better still, Sheela, like Trump, knows how to harness deception and exaggeration as weapons of destabilization. An extravagant threat is a win-win proposition. If your opponents take you at your word, they’re chumps. And if they think you’re a clown, they won’t be prepared for what comes next. The result is an ontological crisis, in which your enemies start questioning what America might look like, what reality can contain. After experiencing the terror of that crisis, it’s natural to want the other side to feel it too. But the only solace to be taken from the tale of Rajneeshpuram is the same reason we can “celebrate” Sheela today: She didn’t succeed.

According to a cooperating witness, Sheela allegedly orchestrated the poisonings of salad bars in 10 restaurants in 1984, affecting more than 700 people, either as a threat against a hostile homegrown community or a dry run for a more serious contagion on Election Day. Later, she pleaded guilty to setting a county office ablaze, assaulting a judge, and the attempted murder of another acolyte whom Bhagwan seemed to prefer to her. To maintain political power over the county, she bussed in 6,000 homeless people from across the country—and when they got too rowdy, she sedated them by tainting their beer with Haldol. It was rumored that she had her loyalists contaminate Antelope’s water supply (the Rajneeshi commune had its own) by liquidating bacteria-ridden beaver corpses and pouring the juices into the reservoir.

She was convicted and given three 20-year sentences, but was released after 29 months. I mention this because of the Trumpian parallels, especially to Michael Cohen who, while not even yet charged with a crime, has been the subject of a criminal investigation for months, an investigation that finally put a bit of the iceberg above water with search warrants served on his home and business. These parallels undermine the argument that Trump is a power to be reckoned with, that he " knows how to harness deception and exaggeration as weapons of destabilization:" and "[a]n extravagant threat is a win-win proposition." It may be in politics, but it isn't in reality. Sheela went to jail; Trump is trying desperately to protect his attorney's documents from Justice Department examination. If this is success, I'd hate to see failure.

But the attraction described in the Slate article is not outcome, but process:

After seeing that “we go high when they go low” doesn’t work, many liberals have been craving a honey badger of their own. That she’s seen in the current day in a neat gray bob, gold-rimmed glasses, and a grandmotherly shawl adds to her political appeal: We’re reasonable, everyday people until given a reason to Hulk out.Yeah, we're reasonable, everyday people who manage to embezzle enough money we can escape to Switzerland and live comfortably after serving only 29 months of a 20 year sentence. And when we "Hulk out," it's only a reasoned response to unreasonable circumstances that we created ourselves. Which is the truth of the situation for Trump as much as it is for we the people who elected him, or allowed him to be elected. James Comey may not quite be on solid ethical ground there, but he's not wrong: we did do this to ourselves, and the duty is on us to correct it. I'm not sure we can't do that by electing officials who will impeach Trump and remove him from office, but Comey is right about where the burden of responsibility falls. And we can't evade that responsibility by letting our inner green monster run rampage across the countryside. That's what Trump wants to do, and he's finding it's not really an option.

So maybe the appeal of Trump is that we, too, want to flex our muscles and assert our righteous and powerful wrath. Maybe we have decided that when they go low, we can't go high, that we can't keep bringing a knife to a gunfight (not that that observation did Sean Connery's character any good, ironically). But that's only because we want to be what Trump imagines he can be, what he sold to us as a possibility: powerful without consequences, vengeful without blowback, assertive without loss. Michael Cohen has reportedly been a "fixer" for people besides Trump; now it's turning out what he "fixed" is not staying fixed, because it primarily depended on staying hidden. Nothing connected to the President of the United States stays hidden, especially these days. Kennedy's affairs would not be gentleman's secrets today, and Trump's affairs cannot be made invisible by the application of cash and the empty threats of litigation. Cohen's reputation seems to have rested on Trump's bullying; but that only works if people are scared. Stormy Daniels is no longer scared.

And we are no longer that admiring of the President. Oh, some people are, but some people went to their graves (or will, yet) convinced Richard Nixon wasn't that bad and got a raw deal. Is this an "ontological crisis" where we must question what America can actually look like, what reality can contain? As one historian noted, if we were to repeat the Civil War today, 8 million Americans would be dead at the end of it. Are we really moving in that direction, toward that crisis? Can our reality contain 8 million of our own citizens dead at the hands of our own government (the usual formula for denouncing Assad in Syria is that he used chemical weapons "on his own people")? We're nowhere near that, yet Trump is supposedly warping the fabric of reality itself? Please.

Our biggest problem is we've awoken to find the country is not an extension from sea to shining sea of our friends and family. People who've obviously never set foot outside a major U.S.urban neighborhood denounce rural Americans as xenophobic and bigoted, as if the neighborhoods of Boston that erupted in violent response to school busing have changed all that much in the intervening decades, as if racism were known only in the backwoods of Mississippi and not in a Starbucks in Philadelphia. Rural white voters, we still tell ourselves, put Trump in office, although in truth those states gave Trump an edge in the electoral college by slender margins; it's just as valid to say urban voters didn't turn out for Clinton, and that tipped the balance; but we prefer the argument that makes "them" complicit, not "us" responsible. When they go low, we don't like to realize that we go low, too.

Some of Comey's arguments about leadership are an attempt to make that rather Niebuhrian argument:

A further consequence of modern optimism is a philosophy of history expressed in the idea of progress. Either by a force immanent in nature itself, or by the gradual extension of rationality, or by the elimination of specific sources of evil, such as priesthoods, tyrannical government and class divisions in society, modern man [sic] expects to move toward some kind of perfect society. The idea of progress is compounded of many elements. It is particularly important to consider one element of which modern culture is itself completely oblivious. The idea of progress is possible only upon the ground of a Christian culture. It is a secularized version of Biblical apocalypse and of the Hebraic sense of a meaningful history, in contrast to the meaningless history of the Greeks. But since the Christian doctrine of the sinfulness of man [sic] is eliminated, a complicating factor in the Christian philosophy is removed and the way is open for simple interpretations of history, which relate historical process as closely as possible to biological process and which fail to do justice either to the unique freedom of man or to the daemonic misuse which he may make of that freedom.

Reinhold Niebuhr, The Nature and Destiny of Man: A Christian Intepretation, Vol. I (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press 1996), p. 24.

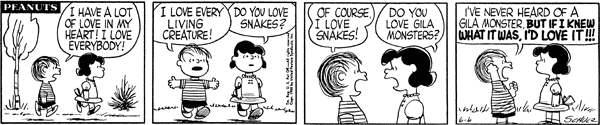

And while I think it's a valid argument, it's a bit out of place here. Out of place, but not wrong; just as the admonition to "go high" when they "go low" is not wrong, but may be out of place. We are, or should be, better than Trump and his supporters, people who don't care what Trump does or says, so long as they perceive they have "won." But going high when they go low presumes a commonality of purpose, a unity of mind, that seldom truly exists. Martin Luther King, Jr. led a social movement that was a religious movement at its core. He describes the process of preparation it took to march in the streets of Alabama or Georgia, the work it took to get people ready to take the blows and the jeers and the punishment without striking back. You don't win these arguments by telling people to be nicer than the opposition; that too easily turns into an argument to think yourself better, to be haughty against their "crudity." That's still the argument of division. It's the same thing as being concerned that America is divided between urban and rural, between xenophobia and tolerance, between bigots and lovers of all races. That way lies the argument that they hate everything, we love everything, which ends up like this:

We go high because it is best for us, not because it always wins the argument. We go high because winning isn't everything. We go high because whenever we release our Hulk, everything ends up smashed and broken and we end up with regrets, not the thrill of victory.

No comments:

Post a Comment