EschatologyI am looking forward, now, to what is coming; not backward, to what has happened, nor sideways, to what is happening now (and should be; or shouldn't be). This is quite unbidden on my part. I wanted to hold this off until a more seasonable time. But it seems that isn't up to me to decide.

Be watchful over your life; never let your lamps go out or your loins be ungirt, but keep yourselves always in readiness, for you can never be sure of the hour when our Lord may be coming. Come often together for spiritual improvement; because all the past years of your faith will be no good to you at the end, unless you have made yourselves perfect. In the last days of the world false prophets and deceivers will abound, sheep will be perverted and turn into wolves, and love will change to hate, for with the growth of lawlessness men will being to hate their fellows and persecute them and betray them. THen the Deceiver of the World will show himself, pretending to be a Son of God and doing signs and wonders, and the earth will be delivered into his hands, and he will work such wickedness as there has never been since the beginning. After that, all humankind will come up for their fiery trial; multitudes of them will stumble and perish, but such as remain steadfast in the faith will be saved by the Curse. And then the signs of the truth will appear; first the sign of the opening heavens, next the sign of the trumpet's voice, and thirdly the rising of the dead--not of all the dead, but, as it says, the Lord will come, and with him all his holy ones. And then the whole world will see the Lord as He comes riding on the clouds of heaven....--The Didache

What I am looking forward to, of course, is Advent. It's coming in a few more weeks, approaching faster and faster as it seems to every year, announcing chaos and recovery, promise and disaster, all over again. The peace and joy of a Currier & Ives or Dickens Christmas; but that is impossible. The frantic pace of the busiest holiday season of the year will bear down like a freight train, loaded with the heaviest expectations perfection, a season that seems more and more less about relaxing, more about "getting it right this time." Time will soon become all about sending out packages early, making purchases you can't really afford, signing Christmas cards or writing the "Christmas letter" and finding the address list from last year or the year before and fitting in all the "holiday" events that crowd the calendar. One of the efforts of being an adult is learning to wear responsibility gracefully; and the expectations of the season are all bosh, easily enough cast aside if one wants to. But not so easily cast aside, either; we want to keep the holiday in its proper place. Maybe that gets harder to do because the merchants put the symbols of the season out in October now, and before Thanksgiving you can already hear the holiday hard on your heels, breathing down your neck, making you think you're going too slow if you aren't already running at full speed. Maybe it gets harder to do because we really like that Currier & Ives/Dickens vision, and just once again, before we go, we'd like to live in it as we did when we were children.

So maybe we should blame Romanticism again. If the child is father to the man, why can't the child just go away now, and let us be men and fathers? (I don't presume to speak for women here.)

Time accelerates as we age; or it seems to. Christmas that was once so far away it seemed it would never arrive, seen from November, now seems over and done with by Hallowe'en, and only the pressure of enjoying the season and cleaning up afterwards is left. Time is precisely my subject here. Christianity is a religion saturated in time. It's kergyma is the adventus; but we prefer it to be the eschaton. That is coming, too, in a few weeks; before the adventus, oddly enough. At the end of the season of Pentecost, the church celebrates the Reign of Christ. The reign of Christ is the eschaton in most popular theologies. It is the time that is here but is not-yet, the event that has come, is coming, and is to come. It is the event we prefer because we think we can control it, or that at least it will control everything. The adventus is the event we cheer, but we fear it; because we can't control it, and because it means a beginning, a new thing is about to be done, and we don't know where that will lead.

Adventus is the arrival of someone long anticipated, of the one who brings blessing just by their presence, of the person we have most looked forward to seeing because now everything begins. But the adventus brings the day of the Lord, when what is done in secret stands revealed, when what is whispered in houses is shouted from rooftops. Adventus is when nothing we have tried to hide, can remain hidden any longer. Adventus is the arrival of power, of true power; and we secretly fear this arrival, just as we fear any power we think we cannot control.

Eschaton, on the other hand, is apocalypse, but in the apocalypse lines are drawn and we are sure of which side we stand on. Eschaton is the end of things, but not the end for us, only for them. Eschaton is when we see justice done, and justice means "just us," and what seems just to us. Eschaton is when our enemies get what is coming to them. It is the unleashing of power, and we are sure we won't be on the receiving end of that release. Adventus is when the ruler arrives, the ultimate power, and sets things right. One is clearly a riskier proposition than the other.

The kerygma of the gospel, the proclamation of Jesus, is that the kingdom of heaven is at hand. This was first understood as the adventus, but when the cosmic ruler did not descend into time again and set history aright, the adventus became the eschaton, and we looked forward not to the arrival but to the ending. And ever since, Christianity has turned erratically around the twin poles of eschaton and adventus, so that even our liturgical calendar reflects the "time being."

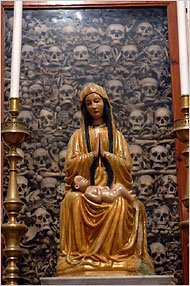

The eschaton prompts us to look forward; but the adventus prompts us to look backward. We don't have many traditions associated with the last Sunday of Pentecost; certainly not as many as we have for Advent. When I served a church here in Houston with deep German roots, I kept the Tötenfest on the last Sunday of Pentecost, but there were no traditions associated with it. I had to invent my own ritual to honor the dead. Advent, however, was another matter, and everyone had their job to do in decorating the church, or preparing the seasonal music and the choir "cantata service" (even if the choir was only 7 rather weak voices) and the December suppers and carol sings (even if only 5 or 6 teenagers could be browbeaten into attending). For the adventus, everything had to be done as it had been done; the eschaton was largely overlooked in looking forward to repeating the traditions and actions and rituals of the adventus, which was all neatly packed up and put away again by December 26. Neat and tidy as a pin. The Kingdom of heaven is at hand, and it will come decently and in good order.

Except it won't, of course: the Day of the Lord is the adventus and the eschton, the arrival and the end, the beginning and the departure.

Christianity is not a doctrine, not, I mean, a theory about what has happened and will happen to the human soul, but a description of something that actually takes place in human life. For 'consciousness of sin' is a real event and so are despair and salvation through faith. Those who speak of such things (Bunyan for instance) are simply describing that has happned to them, whatever gloss one may want to put on it.--Ludwig WittgensteinSo how should we then live? As Wittgenstein points out: "Religion says: Do this!--Think like that!--but it cannot justify this and once it even tries to, it becomes repellant, because for every reason it offers there is a valid counter-reason. It is more convincing to say: 'Think like this! however strangely it may strike you.' Or 'Won't you do this?--however repugnant you may find it.'" Which brings us back to Jonathan Edwards, it seems. It is a reading I find more consistent with the Biblcal story, as well. When God approaches Abraham, God doesn't give Abraham a set of guidelines to follow to be found worthy of God's presence. God simply makes an offer: " 'Leave your own country, your kin, and you father's house, and go to a country that I will show you. I will make you into a great nation; I will bless you and make your name so great it will be used in blessings.' " (Genesis 12: 1b-2, REB) The covenant made with Abraham is continued through Moses, and the laws are better understood as "Think like this!" and "Won't you do this?" than as "Do this!" Otherwise the law is not sweet as honey in the mouth, as the Psalmist sings. No wonder we prefer the eschaton: it gives us a clear responsiblity, and in fact relieves us of responsiblity, as the adventus of the King will mean the end of our duties: we can just sit back and watch the show. "Do this" is in fact much easier to follow than "Think like this!"

God has to address the people of Israel through the law, since God cannot walk with every man, woman, and child and make the promises to them God made to Abraham. The laws are not arbirtrary restrictions but a way of life, of abundant life, of what the gospels would later call, in a direct translation of the koine Greek, "life into the ages." Life in time and beyond time, if it is even possible to speak of such a thing; life into eternity. Life ultimately without time.

What would life look like, freed from time? That is the promise of the eschaton, and why we look forward to it. The adventus is the entry of the eternal into time, and that seems to do us far less good. Time is precisely the problem, we think.

Consider this in terms of the Hebrews of time long past, and of present time. In Afghanistan and Iraq we are told it is the lack of police force, military force, judicial force, that allows chaos to erupt in those countries. That is the Hellenistic view: without civilization, without the imposition of order by reason, by the logos, chaos prevails, and waits for a relaxation of the logos, a weakening, to erupt again. It certainly seems true, when you see the world that way. By this reasoning, the adventus comes only after civilization is established; it comes only to reinforce and maintain the status quo. Order first, then morality, ethics, civilized behavior. And where does order come from, except from power?

The story of the Hebrews is different. God calls Abraham to a new land. God hears the cries of the children of Abraham, and picks Moses to be their leader. And in the wilderness, the very antithesis of civilization, when the people complain that they are going to die there, that they have been brought there only to starve, God gives them the Law. But the law is not "Do this!--Think like that!," though it is sometimes interpreted that way. The Law is the guide to life into the ages. It is the way of life, rather than the way of death. It is to be followed because it is good, and because it provides life; not because it creates power which imposes order on disorder. When the Hebrews finally demand a king, like the other peoples around them have, when they finally decide to abandon their system of judges, of wise women and men who settle disputes between parties, God warns them it is a bad idea; and God, it turns out, is right. They insist on someone having power, like the Gentiles do; those who think they rule over others, as Jesus will later say. Be careful what you ask for, is the lesson. The Law is sufficient guide; the Law leads the nation to life, not merely survival.

The adventus is the law, which brings its own eschaton but leads into eternity. Eschaton is death, which produces only an ending, the return of chaos and the end of the reign of the Greek logos. Creatures of time that we are, it is no wonder we chase after the eschaton, and worry about the arrival of the adventus, and try, year after year, to wrap it in swaddling clothes and childhood memories and sugary blankets and keep it as domesticated, and undisturbing, as possible.

Keep awake, therefor; you don't know when the hour will come.

No comments:

Post a Comment