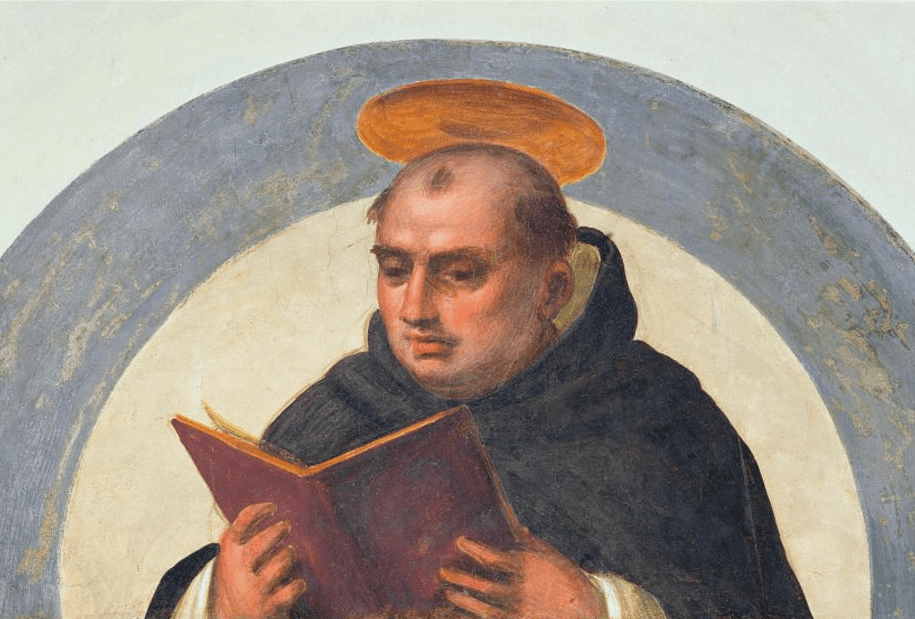

"Three things strike me about one of history's Christians, Thomas Aquinas. (1) He was a friar, a monk; (2) he was a theologian; (3) he was a mystic."I will leave it to you to read about the brief section on the conditions that surrounded his role as a theologian but it is as a mystic that, as actually turned off by Aquinas's theology as I am, I find something that is reported about him late in life as leading me to respect him. Rahner gives a brief mention of it.

"When we speak of Thomas as a mystic we do not mean that he had frequent ecstasies or visions or that he was a little introverted or overly concerned about his own experiences. There seems to he nothing of this in his writings. Yet Thomas was a mystic. He knew about "the hidden Godhead," Adoro te devote, latens deitas (Devoutly I adore thee, hidden Deity). He knew the hidden God. He spoke of the God who pervades and determines everything in silence. He spoke of a God beyond everything holy theology could say about him. He spoke of the God he loved as inconceivable. And he knew about these things not only from theology but from the experience of his heart. He knew and experienced so much that in the end he substituted silence for theological words. He no longer wrote, and considered all that he had written to be "straw." As he lay dying, he spoke a little about the Canticle of Canticles, that great song of love, and then was silent. He became silent because he wanted to let God alone be heard in lieu of those human words he had spoken for us.

Thomas lives. He may seem far away but he is not in reality, for the community of saints is close. The saints come to us overshadowed by the brilliance of the eternal God into whom they have plummeted through the centuries. But God is not a god of the dead but of the living, and whoever has gone home to him, lives. And so Thomas lives. The question for us is: Does our faith live? For it is through our faith that Thomas can become part of our own life."

It has to stand as one of the rarest of things for an academic, a scholastic, a writer of a huge, major piece of thought that took enormous effort, both in the preparatory study and in the writing, revising, editing (with a friggin' quill pen, not a word processor or even text editor) and final draft, to then declare that his enormous, impressive, life's work is as nothing, mere "straw" something that later hierarchs would ignore as they gave that straw a status which became totalitarian in its potential oppressiveness, the opposite of the freedom which is promised to be a result of knowing the truth, why Catholic right-wingers pretend that they study and take Aquinas dead serious and apply the writings that he more or less repudiated, himself, to modern life, looking in it for means of opposing, for example, the rights of women, prisoners, workers, the poor. I think if Aquinas had any idea of the use his writings would be put to in later centuries I think he wouldn't have started to write it.

So I can think well of Thomas Aquinas but not for the reasons most people would. I disagree with much of what he wrote and I think the use that has been put to has been generally unfortunate. I honor him for that great act of humility, of honesty, of giving up everything he had, what he had created. I think in the end anyone, modern theologians as well as those of the 13th century and the fifth, need to understand that as cool as they want their thinking to be, as removed from corrupting biases and a priori considerations, we are not a party to the perfect knowledge that would be required to do that, everything we think, everything we want, everything we want to be true or feel we must hold to be true is a product of our own minds, our pasts, our own experiences and there is nothing to be done about that. It is as true for the hardest of hard science and mathematics and even more so as we deal with more complex realities than those most reputable of modern idols in our imaginations deal with.

When I got up this morning, I have to say, writing about Thomas Aquinas was nothing I expected to be doing.

The bold bits, above, are from a sermon by Karl Rahner. The rest is from a post by Thought Criminal. This should have been a comment on that post; but I knew it would run too long, so I brought the post over here.

I read an account of Aquinas after he'd finished the Summa, a book I've never essayed but should. The story was he had a vision which rendered all he'd done as straw (so it conforms to that extent with Rahner's knowledge), and he never wrote another word. It's extremely strange to think of Aquinas as a mystic. His theology was grounded firmly in the 13th century and in the then newly-discovered (thanks to its preservation by the Muslims) works of Aristotle. Aristotle pretty much upended Christian theology, which battled from then on between Neo-Platonism and Aristotelianism. Neo-Platonic theology I have read, and it's (by modern standards) excessively bizarre stuff. Aristotle is almost the anti-NeoPlatonism. I can understand mysticism in the context of neo-Platonism; but in the context of Aristotelianism, it's bizaare almost to the point of unthinkable.

But here we are.

Still, if you're looking for the "angels dancing on the head of a pin" stuff, you're looking at Platonic theology, and likely through the lens of Aristotelian philosophy. But Whitehead is still right; even Aristotle is just a footnote to Plato. Saying that is not saying it's a good thing; it's just true.

But I'm interested in Aquinas as a mystic. Francis was not known for his mysticism; even though he's the first person to have reportedly displayed the stigmata, the wounds of Christ from the cross. That's usually considered a sign of Christian mysticism, although Christian mystics almost uniformly decline to endorse signs of the presence or even actions of God. Francis didn't promote his stigmata, or present them as proof of anything. His followers, his fellow monks, did that. Aquinas, equally, didn't write an account of his experience. Instead, he stopped talking.

It's tempting, in modern times, to connect that silence to the ending of Wittgenstein's Tractatus:

What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.

But Wittgenstein was not advocating mysticism; rather, he was trying to limit what philosophy could discuss, what language could converse about. His effort, I am more and more convinced, was not that different a goal than what Hume had in mind. But I don't think he meant to stop all discussion of human experience, any more than Hume did. Wittgenstein just wanted to be sure we understood what we meant when we discussed our experiences, and how much we presumed (but shouldn't) in our discussions. I think this line of analysis bleeds over into Derrida's assault on the primacy of logos in Western philosophy; but I'm not trying to open a seminar on modernist philosophy. I'm trying, instead, to consider the limitations of language, and the broadness of human experience.

Most of Christian mysticism struggles with the constraints of language. "The Cloud of Unknowing" approaches this by inventing a word ("unknowing") and trying to make a positive concept of it (it is neither ignorance nor blankness nor denial of knowledge, but it is a true experience of God). The Hebrew scriptures do something similar, as when God is present to Elijah. There are the elements of the theophany familiar from Moses atop Sinai: fire, earthquake, and storm. But each event is described, and the story tells us God is not in any of these things, though they are real and are "signs" of the presence of God. When God appears in the throne room of Isaiah's vision, God is there but not there, because the doxa, the glory, of God makes God obscure. In Ezekiel's vision God erupts from the Temple in Jerusalem on a throne chariot impossible in its physical details but metaphorically representing God's freedom to be anywhere and everywhere at once or at any time. And again, God's glory obscures God's presence, even as it announces and results from that presence. Which can be connected to Rahner's words in his sermon:

To reflect upon Thomas Aquinas as patron of theological studies does not mean merely to think back on some man in History or on his influence in Western thought. Because we are Christians, we are linked to him; we can actually see him as a fellow Christian in the community of saints. Those Christians who have gone before us into the assembly of saints are not dead; they live. They live in perfection, that is, in the true Reality which is also powerful and present among us today. Some of them we can call by name. These Christian men and women can be more real and more important I or its than theoretical principles or abstract ideas. In many ways they are even more real than we are, for they are with God. They love us; we love theta. They are present at the eternal liturgy of heaven, and intercede there for its their brothers.

In comparison to the saints' present existence, their past. history on earth is comparatively of little significance. They now live the quintessence of our life on earth in an eternal form, and the Reality in which they exist is in the last analysis the ground of all reality on earth. They do not belong to the past at all, except insofar as they have lived on earth in past history. Actually they have run ahead, hastened forward into the future, a future waiting for us. To look at a saint., then, is not. to look at something abstract or impersonal, something dead, but rather to sec a concrete person, a unique individual, once alive on earth and now eternally alive, someone who loves and praises, someone who is blessed and redeemed.

Rahner there tries to give words to the ineffable, the inexpressible, that is God. But all he can come up with is "the true Reality which is also present and among us today," and "in the last analysis the ground of all reality on earth." It is the language of theologians, which is to say it's a vocabulary limited even among vocabularies. I would not call it a language game, but I would point out its limitation even among the limitations of language we all strain against. This description is even further limited to those conversant with the concept of "true Reality," even if they can't agree on just what that concept is. "What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence." Still not what Wittgenstein meant, but as Humpty Dumpty asked Alice: "Who's to be the master, then? You, or the word?" Lewis Carroll is an underrated philosopher; and maybe a theologian, too.

I'll have to think about that.

I would say that any good theologian is necessarily a mystic, since the urge to reflect on, and express, the phenomena of God and the World necessarily leads to an appreciation of the limits of language and theology, of the point at which one can only be silent.

ReplyDeleteI have a greater regard for St. Thomas Aquinas than our friend TC, I suppose, since I was born into a time of his diminished influence, and I encountered him as a novelty rather than as an authority.

In college, as a Protestant, I first came across the scholastics in the "Medieval" segment of a History of Philosophy curriculum. I was intrigued, but I had no context for "the thirteenth century" other than its place on a time line.

A year or two ago I started some reading on the foundation of the University of Paris, for personal reasons you are aware of, and the meaning of that descriptor "scholastic" suddenly became blindingly obvious. St. Thomas was a teacher, and his summa was just that, a summary, a curriculum, in the form of a disputation over opposing theses.

It has always struck me that the form of each question is remarkably open. A question, a series of answers with reasons (which typically are not the orthodox answer), a reply to those answers, and a series of responses arguing why each of the original answers was wrong. In one sense it can appear stiff and pedantic. On the other hand, it means that something like forty per cent of the summa consists of arguments for unorthodox propositions. And the form is never mere assertion, but an appeal to reason, a faculty that our medieval forebears arguably gave greater credence to than ourselves.

The Summa, like all academic theology, is of course a different matter from life as a follower of Jesus. I find it helpful that Christian life need not be lived apart from intellectual and critical underpinnings. And I find that especially true given how unhinged our political life has become when thought and human sympathy suddenly become subject to "the triumph of the will."