Yeah, pretty much...

There are two ways of defining the worship space in Christianity, and the difference turns on whether you have a congregation led by a priest, or by a pastor.

Generally speaking, if the church has a priest, then the worship space is the property of the church, and even the form of worship comes from the church hierarchy. The classic example is the Roman Catholic church, but Episcopalians are not that different from the Roman liturgy, and Lutherans show a surprising similarity to the Catholic liturgy (surprising only because what most people know about Lutherans is Garrison Keillor, who ironically isn't). A church led by a pastor lays claim to the worship space; the pastor is allowed charge of it, but within more distinct restrictions. (A favorite short story is comprised of letters to a C of E rector about who in the congregation will get to put up what decorations when for the Christmas season, in the worship space. We're never quite discussing absolute control here.) I've seldom seen, for example, a Protestant worship space that didn't include an American flag near the pulpit or at least flanking the chancel. Some churches try to balance it with a "Christian" flag, something I think flag makers invented in the '50's to sell more flags, but the intent of the national flag is clear.

When I was still in a pulpit in Houston, I was asked to host a visit from a visiting German pastor, because of the historical connections between the UCC and the German Evangelical and German Reformed churches. The pastor was a woman, younger than me, and she asked why we had a flag beside the pulpit. I explained I didn't like it, and she confessed she thought it disturbing, especially given the history of Nazi Germany that she, like me, didn't remember but had learned. Her escort/driver for the day immediately launched into a defense of the flag in the church, distinguishing it from any sense of state intrusion into worship by saying the flag represented people who had died for American freedom. He was of my father's generation, and the gap between the three of us was obvious. Once a year in that church we celebrated "Scout Sunday," because the church sponsored a Boy Scout troop. It required (and here, especially, is where the congregation controlled the worship space and the order of worship, at least once a year) the trooping of the colors, which meant the American flag and various Boy Scout colors were marched into the chancel from the nave, and all stood and recited the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag before worship could commence. The strongest protest I could mount was to stand silently during the pledge, my hands at my side.

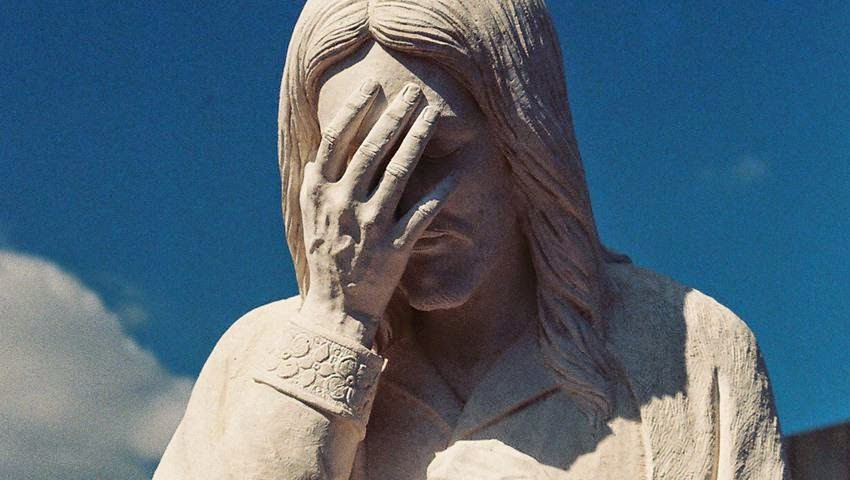

I bring this up because of this:

Pastor Mack Morris wanted to take a stand. Preaching in front of his Mobile, Alabama, congregation on Sunday morning, positioned just to the left of an American flag, he declared that he was sick and tired of the way clothing brand Nike had, in his view, disrespected America and its people.

“The first pair of jogging shoes I wore were Nike jogging shoes,” he told his congregation, “That was in the early ’80s. I’ve been wearing Nike jogging shoes since 1980. I got news for you. I’ve bought my last pair of Nike shoes.” He produced two branded items — a Nike wristband and a headband. Then he cut them up right there at the pulpit.

His audience’s response? Raucous applause.

I'm not really surprised by that, but then, I remember when pastors could lose their place if they just mentioned from the pulpit that maybe the Vietnam War wasn't such a good idea after all, or that (especially in the South, where I grew up, but just as common elsewhere, I think now) Martin Luther King might have a point (he became, like all saints, a saint only in death). Tara Isabella Burton thinks this one event is not just a protest against Colin Kaepernick or Nike, but a "powerful symbolic act":

It reveals the virtually unprecedented degree to which white evangelical theology, and an extremely narrow (white, conservative) understanding of “patriotism,” have converged in the post-Trump age. White supremacy, evangelical identity, and a distinctively Christian form of nationalism have combined.This "convergence" is unprecedented only if you have no knowledge whatsoever of the history of Christianity in this country. The understanding of "patriotism" has been narrowing since at least the end of World War II. If you watch as blithe an example as "The Best Years of Our Lives," you won't find one John Wayne-style character giving a speech about liberty and victory a la Wayne's speech by Davy Crockett "The Alamo" (a speech that makes me long for the bluntness of the real Davy Crockett, who told a crowd after he lost a political race: "You may all go to hell, and I will go to Texas." Even if it isn't true, it looks great on a coffee mug.) There's even a scene with a dissenter against the war, after it has ended; he still holds to a conspiracy theory about why it happened and why it didn't need to. England tries to hide the complicity and sympathies of its ruling class for Hitler; America tries to ignore that there was not, after all, complete unanimity about the "Good War."

Christianity and nationalism have been locked in an unholy marriage for as long as I can remember. God wanted us to win World War II, and God wanted us to be prosperous (and white) after the war; God wanted us to fight the godless commies and Korea and Vietnam, and God didn't look too kindly on black preachers stirrin' up the black folk. Ah, yes, I remember it well.

Burton recognizes this, to some degree:

John Fea, a professor of history at Messiah College in Pennsylvania and author of Believe Me: the Evangelical Road to Donald Trump, told Vox in a telephone interview on Thursday that Morris’s actions represented a combination of two elements. The first, he said, was “conservative evangelicals’ commitment to the idea that America is a Christian nation, and that somehow the American flag not only symbolizes generic nationalism but that the nation was founded by God, that it’s a nation created by God. So [people think], how dare Colin Kaepernick take a knee.”Well, yes, Trump is a loose cannon on the deck of the ship of state, and everyday Raw Story runs another video about another white person have a public breakdown about their fear of a brown planet, public displays obviously (?) connected to the behavior of the President (sometimes the causal connection there is in the eye of the beholder. And, as Andrew Bacevich points out, Trump really is a continuation of history, but a rupture with it.). But is this "unprecedented"? No, of course not.

Secondly, he said, “Christian nationalism has always been connected with whiteness. It has always been about [the idea of] America’s founding by white Christians.”

These ideas, Fea said, have existed throughout American history. But Donald Trump’s campaign and election have them to the fore. Furthermore, he said, we’re seeing an unprecedented relationship between the president and the evangelical religious establishment, in which pastors take “marching orders” from Trump’s own discourse.

And I keep thinking of the counterfactual, which no doubt exists somewhere in America: what of a UCC congregation where the pastor preaches just the opposite of what this pastor in Alabama said, to the approval of his congregation. Jeremiah Wright pastored a UCC church of over 8000 members, and made many a fiery statement from a more distinctly left position on the political spectrum. Until Barack Obama ran for President, who had ever heard of Jeremiah Wright? Why were his sermons (in full, not in the cut-and-paste versions released in the campaign of 2008) never a signifier of greater, more serious, or even more disturbing, things? Because he was black? Because he was UCC? Because he was "liberal" and therefore represented nothing beyond his parishioners?

And who does Mack Morris represent, beyond Woodridge Baptist Church?*

*which seems, curiously, to have removed itself from the internet. TIB notes the video of the sermon has been removed from Vimeo; as far as I can find, the website of the church has been removed, too.

I don't go to mass enough so I know if there's a flag in the church, I do know that during my parents funeral masses they removed the flags from their coffins (both of them vets of WWII) and replaced it with a pall. I don't know if that's related to this or not.

ReplyDeleteI don't like to see a flag in a church because of lots of things. Right now it's because I don't think democracy can exist in the United States under our Constitution unless a sufficient number of people believe that many things necessary for democracy come most typically from religious values which are held to transcend man-made laws. Certainly some of the ones that rule in the law, as opposed to The Law.

That said, the substitution of Christianity for an imitation called the same thing but just a modern, American style secular state paganism should be resisted. I'm kind of scandalized at how widespread that state religion is.

Admittedly I'm going on memory, but I think I noticed the lack of a national flag in the Episcopal church I attended for a few years. The basis of my "analysis" could be undone with a few counter-examples, but still, the idea persists, to me: a church that identifies with its congregation (i.e., a "congregational" polity) is more inclined to put up a flag and display it in worship, than an episcopalian polity. IMHO, anyway.

ReplyDeleteAnd the substitution of Xianity for an imitation has been going on as long as I can remember, and as best I understand American (at least) history. I agree, it is to be resisted. I'm just not as shocked as TIB to notice it, and I'm a little tired of right-wing churches being the exemplar for all of American Xianity, while we're on the subject.